Gut Check! How Ruminant Digestion Powers Regenerative Ranching

Learn why ruminant gut health is critical for cattle wellness. Discover how the four-chambered stomach, rumen microbiome, and grass-based diets create healthier Texas beef.

GRASS FED BEEF EDUCATIONREGENERATIVE AGRICULTURETEXAS AGRICULTURE

Troy Patterson

11/16/20257 min read

Walk into any Texas feedlot and you'll smell it before you see it—the acrid stench of cattle standing in their own waste, fed high-grain diets their digestive systems weren't designed to handle. Now visit a regenerative ranch where cattle graze diverse pastures, and the difference hits you immediately. The animals look different, act different, and produce beef that tastes different.

The secret? It starts in the gut.

Ruminant digestion represents one of nature's most sophisticated biological systems. When that system functions properly on grass, everything from animal health and performance to beef quality improves. When disrupted by grain and antibiotics, problems cascade through the entire operation.

Understanding the rumen and the lower gut explains why regenerative ranching works—and why industrial cattle feeding fails both animals and consumers.

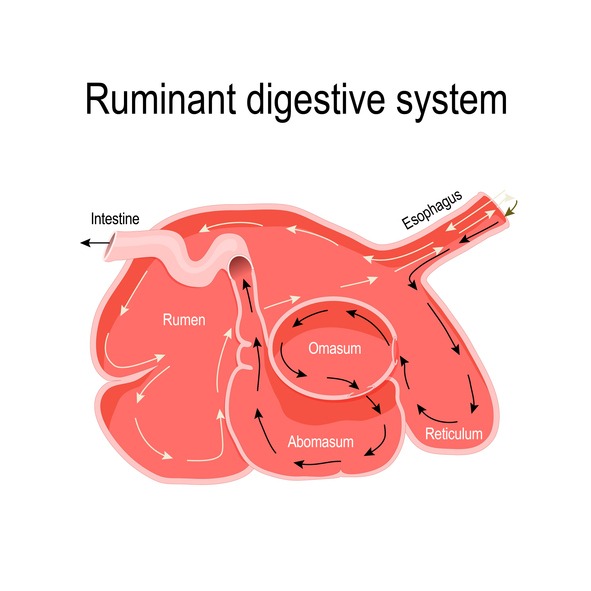

The Ruminant Digestive System: Four Chambers, One Mission

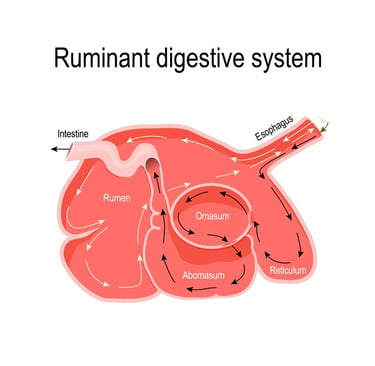

Cattle and other ruminants evolved a digestive system unlike any other mammal. While humans and pigs have simple stomachs, the ruminant digestive system contains four specialized compartments that work as an integrated fermentation facility.

The Rumen: Nature's Fermentation Vat

The rumen dominates the ruminant stomach, holding 40-50 gallons in mature beef cattle. This massive chamber functions as a living bioreactor where trillions of microorganisms break down fibrous plant material. The rumen microbiome contains over 200 bacterial species, plus protozoa, fungi, and archaea working in complex microbial communities.

These rumen microbes perform fermentation that converts cellulose from grass into volatile fatty acids the animal absorbs for energy. Without this microbial population, cattle couldn't extract nutrients from pasture. The bacteria present in the rumen literally make ruminant digestion possible.

The Rumen and Reticulum: The Fermentation Team

The reticulum works closely with the rumen, catching foreign objects and regulating particle size. Together, the rumen and reticulum form what ranchers call the "fermentation vat" where the majority of microbial digestion occurs.

The rumen wall absorbs the fatty acids produced during fermentation—primarily acetate, propionate, and butyrate. These volatile fatty acid molecules provide 60-80% of the energy cattle need for maintenance and growth. The rumen environment maintains a delicate pH balance, ideally between 6.0-7.0, supporting diverse microbial populations.

The Omasum and Abomasum: Finishing the Job

After fermentation, partially digested feed moves to the omasum, which absorbs water and nutrients. The abomasum functions like a human stomach, using hydrochloric acid and digestive enzymes to break down microbial proteins and remaining feed particles.

From there, digestion continues in the small intestine where the animal absorbs amino acids, vitamins, and minerals. The digestive tract of cattle extends about 150 feet, providing extensive surface area for nutrient absorption. Understanding this digestive physiology explains why diet composition matters so much for cattle health.

The Bovine Rumen Microbiome: Trillions of Tiny Workers

The bovine rumen microbiome represents one of the most complex microbial ecosystems on Earth. Scientists estimate that microbial biomass in the rumen of a single dairy cow can weigh 10-15 pounds.

Cellulase-Producing Bacteria

Specific bacteria in the rumen produce cellulase enzymes that break down cellulose, the structural component of plant cell walls. Species like Ruminococcus and Fibrobacter specialize in digesting fibrous material. Without these cellulolytic bacteria, cattle couldn't digest grass.

The rumen microbial ecosystem functions through cooperation. Some bacteria break down cellulose into simple sugars, others ferment those sugars into fatty acids, and still others synthesize amino acids from non-protein nitrogen. This metabolic teamwork converts grass into high-quality beef protein.

The Rumen Microbiota and Protein Synthesis

Here's something remarkable: rumen microorganisms can synthesize protein from simple nitrogen sources that non-ruminant animals can't use. This means cattle build muscle from grass that contains modest protein levels because the gut microbiota manufactures microbial protein.

As these bacteria reproduce, die, and pass into the abomasum and intestine, the cattle digest them. This microbial protein provides much of the amino acids beef cattle need for growth. The rumen microbial communities essentially serve as a protein factory powered by grass.

Vitamin Production and Nutrient Cycling

A healthy rumen microbiome synthesizes B vitamins and vitamin K. The gut microbiota of cattle produces nutrients the animal can't manufacture on its own. Dairy cattle with robust rumen microbial populations don't need vitamin supplementation—their digestive system handles it naturally through fermentation.

Rumen Development: From Calf to Adult

Newborn calves aren't born as functional ruminants. Rumen development takes months, and early gut colonization by beneficial microbes sets the stage for lifetime health.

The Young Calf's Digestive Journey

At birth, a calf's rumen is small and non-functional. Milk bypasses the rumen through the esophageal groove, flowing directly to the abomasum. During the first weeks, the early gut resembles that of non-ruminant animals.

As the calf begins eating grass and hay, the rumen gradually develops. Microbial colonization accelerates, the rumen wall thickens, and fermentation capacity increases. By 3-4 months, rumen fermentation provides the majority of the calf's energy needs.

Maternal Influence on Gut Health

Research shows that dairy cows and beef cattle pass beneficial gut bacteria to calves through contact and environmental exposure. Calves raised on pasture with their mothers develop more diverse rumen microbiota than calves raised in confinement.

This maternal transfer of microbes helps establish healthy rumen microbial communities that support lifetime health and performance. The gut of the dairy or beef calf develops differently depending on early experiences, affecting feed efficiency in beef cattle years later.

What Disrupts Ruminant Gut Health

Modern cattle feeding practices often work against the ruminant animal's natural digestive capabilities. The consequences affect gut health, overall health, and production efficiency.

High-Grain Diets and Subacute Ruminal Acidosis

When cattle fed high-grain diets consume large amounts of rapidly fermentable starch, rumen pH drops below 5.5. This acidic environment kills cellulolytic bacteria and favors lactic acid producers. The result: subacute ruminal acidosis (SARA), a condition plaguing feedlot operations.

SARA creates a leaky gut condition where the rumen wall becomes inflamed and permeable. Endotoxins from dying bacteria pass through the compromised gut barrier into the bloodstream, triggering systemic inflammation. The effects on gut health cascade throughout the animal, reducing immunity and increasing disease susceptibility.

Dairy cattle on high-grain diets face similar problems. Lactating dairy cattle pushed for maximum milk production often develop SARA, leading to health and metabolic issues including liver abscesses, laminitis, and reduced fertility.

Antibiotics and the Gut Microbiome

Routine antibiotics don't just kill pathogens—they devastate beneficial gut bacteria. Antibiotic use alters the gut microbiota composition, reducing diversity in both the rumen and intestinal microbiome.

Research on dairy cows shows antibiotics reduce cellulolytic bacteria populations for weeks after treatment. This affects gut function, nutrient absorption, and feed efficiency. The role in health and disease prevention of a diverse gut microbiome makes antibiotic overuse particularly problematic for ruminant livestock species.

Stress and Digestive Dysfunction

Stress from overcrowding, heat, or transportation affects gut permeability and microbial balance. Stressed cattle experience reduced feed intake, less rumination, and compromised gut integrity. The intestinal health of beef cattle declines under chronic stress, making animals vulnerable to pathogens.

On regenerative Texas ranches practicing low-stress handling, cattle maintain healthier digestive systems and more resilient rumen microbial ecosystems.

Reading the Signs: Gut Health Assessment

Experienced ranchers can evaluate the health status of their herd by observation.

Manure Tells the Rumen's Story

Healthy cattle produce firm, layered manure piles with visible fiber. Each "pancake" should stack about an inch thick. This indicates proper rumen fermentation and normal digestive tract function.

Loose, watery manure signals digestive problems—possibly acidosis, parasites, or bacterial infection. Very dry, hard manure indicates dehydration or poor diet quality. Changes in manure consistency reflect what's happening within the rumen and throughout the gastrointestinal tract.

Body Condition and Coat Quality

Cattle with healthy gut function maintain steady body condition on grass. Their coats appear smooth and shiny, reflecting good nutrient absorption. Poor digestion shows as weight loss, rough hair, and low energy—visible signs that gut health isn't supporting production and health.

Rumination Behavior Indicates Rumen Function

Healthy cattle spend 6-8 hours daily ruminating—chewing cud. This behavior indicates proper rumen environment and normal microbial fermentation. Watch a herd at rest; most animals should be lying down, calmly chewing.

Reduced rumination signals rumen disturbances, possibly acidosis or other digestive issues. Cattle health depends on this constant cycle of eating, ruminating, and fermenting.

Restoring Natural Gut Health Through Regenerative Practices

The most effective way to support ruminant gut health is simple: work with the digestive system of ruminants, not against it.

Grass-Based Diets Support Healthy Rumen Microbial Communities

When cattle transition from grain to grass, the rumen microbiome shifts toward its natural composition. Cellulolytic bacteria increase, lactic acid producers decline, and rumen pH stabilizes. This promotes improving gut health throughout the digestive system.

Cattle raised entirely on pasture never experience the gut disruption that feedlot animals endure. Their bovine rumen maintains diverse microbial populations throughout life, supporting consistent health and productivity.

Diverse Pastures Build Diverse Gut Microbiota

Texas ranchers practicing regenerative agriculture maintain diverse pastures with multiple grass species, legumes, and forbes. This plant diversity directly supports greater diversity in the rumen microbiota and human gut microbiota differs fundamentally from ruminant nutrition needs.

Research shows cattle grazing diverse pastures have more resilient rumen function than those on monocultures. The variety of plant compounds feeds different bacterial groups, creating balanced rumen microbial populations associated with gut health and disease resistance.

Natural Minerals Help Maintain Gut Function

Free-choice mineral access supports optimal rumen environment and metabolic function. Sulfur supports microbial protein synthesis, while trace minerals including copper, zinc, and selenium support immune function and intestinal health.

On well-managed regenerative operations, cattle select minerals based on needs, naturally supporting the prevention of digestive disorders and maintaining gut barrier integrity.

The Gut-to-Beef Connection

Rumen health directly affects the beef you eat. Cattle with robust gut health grow efficiently on grass, producing beef with higher omega-3 fatty acids, conjugated linoleic acid (CLA), and fat-soluble vitamins.

The fatty acids produced during grass fermentation influence flavor compounds in beef. Properly grass-fed beef from cattle with healthy ruminant gut function offers cleaner, more complex flavor than feedlot beef from cattle with disrupted digestive systems.

Health implications extend beyond the animal. When cattle thrive on grass with healthy digestive systems, they produce more nutrient-dense beef without antibiotics or growth promotants. This affects human health beyond simple nutrition—it's about food from animals raised according to their biological design.

Why Regenerative Texas Ranchers Focus on Ruminant Digestion

Progressive Texas ranchers understand that animal health and productivity start in the gut. Rather than fighting the ruminant digestive system with grain and drugs, these producers work with natural ruminant feeding behaviors.

They rotate cattle through diverse pastures, allowing proper rest for both grass and rumen microbial ecosystem recovery. They avoid routine antibiotics, building ruminant livestock health through nutrition instead of medication. They select genetics suited to grass-finishing rather than grain-feeding.

The result? Cattle that thrive on Texas grasslands, developing healthy rumen microorganisms, strong gut barriers, and efficient nutrient absorption. These animals produce nutrient-dense beef while building soil health—proving that when we respect ruminant digestion, everybody wins.

From the microscopic bacteria in the rumen to the grass growing in the pasture, regenerative ranching recognizes that health in cattle begins with properly functioning digestive systems. That's not just good animal husbandry—it's the foundation of sustainable beef production and the key to health beyond conventional agriculture.

Texas Grass Fed Farms

Families Deserve Food That Heals, Not Harms

© Texas Grass Fed Farms 2025. All rights reserved.